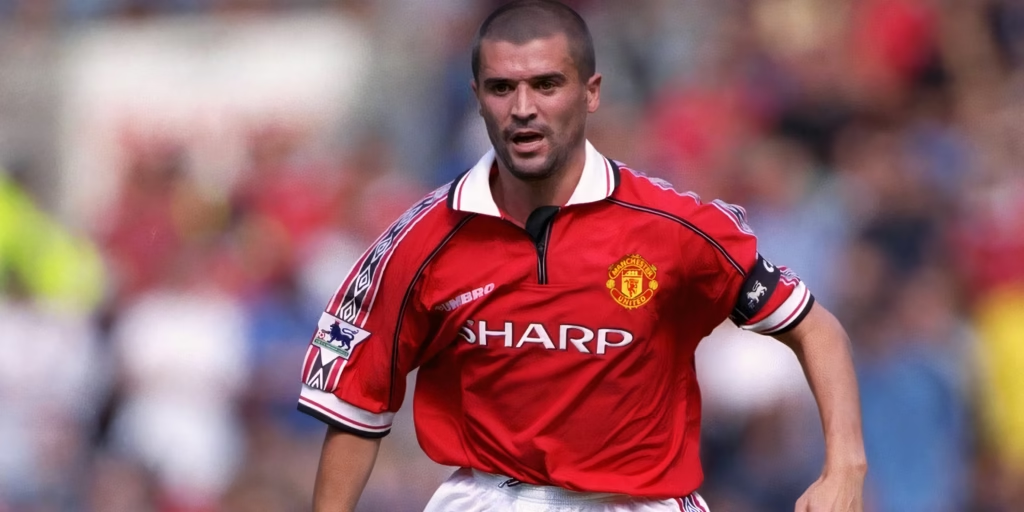

When Roy Keane arrived at Old Trafford in the summer of 1993, he did so as one of the few players in the country who had the potential to step into the midfield partnership of Paul Ince and Bryan Robson and improve it.

That’s a sentence with a punch, the power of which may be lost on younger fans, so allow me to elaborate. Ince and Robson had proven themselves as the best central midfield in the country, and had been ably assisted by Brian McClair in delivering Manchester United’s first league title in 26 years.

McClair was moonlighting in the role due to his fantastic on-the-ball ability for a forward player. Ince and Robson were specialists. Ince was a box-to-box midfielder who would have recoiled in horror if you were to reduce him with a singular role the likes of which todays midfielders are happy to accept. He could do it all and did do it all.

He perhaps only lacked the sort of discipline which would eventually be his downfall in Alex Ferguson’s eyes, but he was versatile when asked to move around the pitch, and never stopped driving forward. His tackles were brave and full-blooded, he was good on the ball, he had a good sense for scoring goals, and a knack of scoring important late goals from time-to-time.

What is there to say about Robson? When he signed, manager Ron Atkinson promised Martin Edwards six years as a midfielder and six as a central defender. The captain had completed twelve years in the middle of the park, defining the box-to-box standard Ince would try to imitate and that we’d see to slightly lesser effect up at Anfield with Steven Gerrard.

Robson was magnificent, and if his prime had been spent in the Premier League era, the headline of this column would have a different tribute. Robson was good enough to walk into an all-time United XI and have the argument be who his partner is. He was good enough to best Maradona when the two came head-to-head.

But Robson was now 36. United needed to plan for a replacement.

They could not have found a better man for the job than Nottingham Forest’s Roy Keane.

Despite Forest being relegated, Keane was sought after by the best clubs in the country. Blackburn had the money and thought they had the deal done. Ferguson managed to pinch the midfielder from under the nose of Kenny Dalglish. In doing so, he’d acquired his most important signing since his last one – Eric Cantona, nine months earlier. He’d arguably never make a more important signing than Keane.

Version One

When I tell you that Roy Keane scored two goals on his home league debut and two on his European debut, you’ll instantly get the impression that this was a different Keane to the one who would screen the defence at the twilight of his career. It would be fair to say he was not as good on the ball as Robson but he had everything else in his game. His energy reserves were full, as opposed to Robson’s which had been depleted through time. He could go, and did, making an instant impression and settling in right away.

United were unstoppable and Keane was influential, memorably scoring a late winner in the Manchester Derby in November.

Eight goals in his first season, and two trophies – the League and FA Cup – were accompanied by the important development of an attitude. He had noticed how teams raised their game against United and he wasn’t going to stand for it.

“What really bugged us was the thought that these guys were out to make a name for themselves by sorting us out,” Keane said in his first autobiography. “Why the **** didn’t they put the effort in every week, then maybe they wouldn’t be playing for ****ing Norwich or Swindon. So there was no rolling over when faced with this stuff. Meet aggression with aggression, then ability would make the difference at the end of the day.”

It is arguably the best sentence to sum up what Keane brought to United. Bryan Robson left to become player-manager of Middlesbrough and Keane was now a fixture in the team, albeit with some deputising for the injured Paul Parker at right-back over the next couple of years, but there was no doubting where his influence laid.

He evolved into the best midfielder in the country and was the unsung hero of the 95/96 campaign. While Peter Schmeichel’s incredible form at one end and Eric Cantona’s divine intervention at the other grabbed the headlines, Keane was the man in the middle. He was the one helping to steer the team through the early weeks when Cantona was still suspended.

It was Keane scoring a late winner against West Ham, it was Keane with two goals against Wimbledon, and it was Keane who was – humorously – sent off for diving at Blackburn. Less humorous, more serious, was the developmental role Keane played in helping the Fledglings settle into the team. Giggs was already there of course but it was Keane who provided the settled platform for the likes of Butt, Scholes and Beckham to buzz around him.

The maturity came with a sense of timing. Keane scored important goals in wins over Newcastle and Leeds, before putting in a man-of-the-match shift in the FA Cup Final against Liverpool. It was a landmark performance that made the manager realise this was his captain-in-waiting.

That moment came in 1997 after the retirement of Eric Cantona. Keane had another superb season as he won his third league title – superb when he was on the pitch, though it was a season disrupted by a persistent knee injury and suspensions. Keane was ruled out of the second leg of the Champions League semi-final with Dortmund – a definitive absence, as United were eliminated.

The result contributed to Cantona’s decision to retire. Ferguson allegedly offered Keane Cantona’s captaincy and his number seven shirt. Keane accepted the first but not the second. He was showing the sort of form which suggested he was growing into the role as United skipper, scoring twice in the early weeks of the 97/98 campaign before he went into an aggressive challenge with Alf-Inge Haaland. Keane suffered a cruciate ligament injury – Haaland stood over him, angrily remonstrating at the original tackle.

The truth was this was reflective of Keane’s personal mood of the time anyway – he’d been involved in fisticuffs with Chelsea players in the last home game and in the week before the trip to Elland Road he’d been involved in an altercation in an hotel.

Version Two

“I was a different person from the lunatic who’d hunted Alfie Haaland 9though I hadn’t forgotten),” Keane said, “I now cherished every moment of my football… I realised as I’d never really done before my lost season that your time in football is finite.”

Keane also explained that the extra time with his wife, daughters and newborn son had convinced him to step back from drinking too much. “I’d clearly identified my own weaknesses,” he said. “As a result I was less tolerant of me.”

He admitted he was hungrier than ever. It was a strong attitude to bring into a dressing room who, without him, had just lost the title to Arsenal.

The team was strengthened with the signings of Jaap Stam and Dwight Yorke. Stam and Yorke were brilliant. David Beckham used the emotion from the 1998 World Cup to fuel one of his best-ever campaigns. But Roy Keane was on a different level to everyone in the league, present on the pitch for all of the last minute goals.

Keane’s personal education included a vital lesson. Economy. He didn’t have to be everywhere to control everything. He could dictate the tempo of the game from a deeper position and make his runs wisely. There were crucial goals – his strike against Bayern in the last European group game ensured qualification – but the assurance in his performance was so strong that if he was not man of the match, a United player had usually done something seminal in his own career to surpass him on the night.

It was the season for it. Andy Cole and Dwight Yorke against Barcelona. Beckham against Inter Milan. For Roy Keane, there was a seminal appearance in a seminal season.

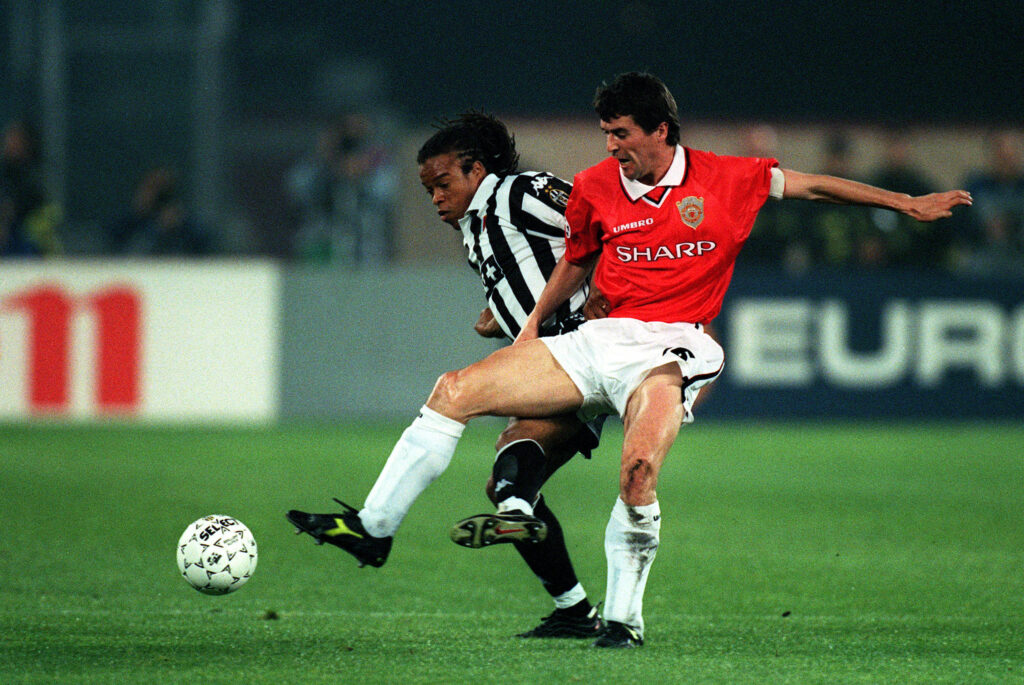

His 9.5/10 weekly average was raised to a 10/10 pinnacle in Turin as he evoked the spirit of Duncan Edwards (“We haven’t come here for nuffin’”), and Bryan Robson against Barcelona, to inspire a turnaround when all seemed lost against Juventus.

He’s the most fantastic player I’ve ever had.

Alex Ferguson after United’s win in Turin

Keane scored the first goal from 2-0 down and ran the show against a midfield containing Zinedine Zidane, Antonio Conte and Edgar Davids. United levelled before half-time and went on to win on the night. Keane’s inspiration was all the more remarkable considering he had picked up a first half booking which would rule him out of the final if United got there.

The club’s official website asked if it was the ‘best ever’ individual performance in a game in the club’s history, and while George Best’s game in Benfica in 1966 probably trumps it, it comes a close and worthy second.

“Pounding over every blade of grass, competing as if he would rather die of exhaustion than lose, he inspired all around him,” Alex Ferguson said. “I felt it was an honour to be associated with such a player.”

United evoked that spirit for one final comeback in which Keane was not present – the game against Bayern Munich.

If there was one black spot against Keane it had been that he had not commandeered in games against Arsenal’s Patrick Vieira the same way he did everyone else. That was corrected with an August 1999 ram-raid of a showing where Keane confronted the French international and scored twice in a 2-1 win – a definitive statement to end the argument, if it were indeed needed.

United stormed to the title and made it three on the bounce in 2001, where Keane rubber-stamped his superiority by starring and scoring in a 6-1 win over Vieira’s Gunners in February 2001.

Earlier that season he’d put in the greatest performance seen in an Ireland shirt since Paul McGrath took Roberto Baggio to school at USA 94, when he inspired his country to a 1-0 win over a Holland team including Clarence Seedorf, Patrick Kluivert and the De Boers.

The result got Ireland into the play-offs, from which they succeeded to qualify for the 2002 World Cup – a tournament that did not go quite so well for Keane.

In Europe, Keane had continued to star – scoring goals, too, one of them a sensational volley against Sturm Graz – but grew frustrated with what he felt was complacency borne from the club’s domestic strolls. He would make bold public statements – “We’re not good enough” after one European exit, and “Away from home our fans are fantastic, I’d call them the hardcore fans. But at home they have a few drinks and probably the prawn sandwiches, and they don’t realise what’s going on out on the pitch” in November 2000.

The frustration began to boil over on the pitch as well. Keane came head-to-head with old nemesis Haaland in a Manchester derby and went in on a high challenge. He was rightly sent off, and wrongly attributed with causing the knee injury which plagued Haaland’s career (it was the other knee).

A year later Keane published his autobiography in which he admitted he had intended to hurt Haaland – remarkably, this earned him an unprecedented five-match ban in late 2002.

Ferguson and Keane used the absence as a convenient moment for Keane to have a hip operation – he had been taking painkillers for a year, though this did nothing to Keane’s on-field performance, as the player was constantly putting himself at risk of long-term damage for the good of his team.

Version Three

If Keane 2.0 had become more economic, Keane 3.0 was completely so. The hip operation impacted his mobility to the extent that the lung-busting runs to join in attacks in case of loose balls dropping to the edge of the box were almost exclusively a feature of the earlier incarnations.

“I’d come to one firm conclusion, which was to stay on the pitch for ninety minutes in every game,” Keane said. “In other words, to curb the reckless, intemperate streak in my nature that led to sendings-off and injuries.”

Keane returned as the team were in a poor run of form, and immediately helped to transform it. Last-minute winners against Chelsea and Sunderland were part of a run of nine consecutive wins which turned the season around. Keane was superb in a 2-2 draw at Highbury which went a long way to helping United retain the title – his seventh, and fourth as club captain, more than any player in United history.

That title marked a transitional moment for United. Chelsea had just been taken over by Roman Abramovich and spent lots of money acquiring players, some of which had been scouted by United. David Beckham was sold and replaced by a kid by the name of Ronaldo. Jaap Stam and Denis Irwin were gone, so too Ronnie Johnsen, as the treble team began to fall apart and get rebuilt.

The following season Arsenal won the league and went unbeaten doing so – failing to win in the head-to-head matches against United, though, one of which was an infamously ugly 0-0 draw at Old Trafford. Keane played his part in a pulsating FA Cup semi-final win over the Gunners and played in the Final against Millwall, which was won 3-0.

United continued to build. Wayne Rooney was brought in. He and Ronaldo showed flashes of skill and also lots of temperamental moments as they struggled to adjust to the increased physicality which came from playing at Old Trafford – just as Keane had in his first season.

On the pitch, Keane remained consistently the best player for the club. Now 33/34, and less mobile, his performance average might have dropped slightly from 9.5 to 8.5, but he was almost always the best player – save for those outstanding individual performances of others – and you always knew that with Keane on the pitch, United would fight as a minimum. His tackling was near-perfect. His range of passing was exceptional. These are skills which are often underrated when Keane’s ability is discussed, and this can only be because of the incredible domination of his character.

He missed the Arsenal home game (after cutting out red meat from his diet, causing an iron deficiency) which went down in history as United ended their unbeaten run – the following three months before the return were dominated by the perception that Arsenal had been kicked off the park by a team who weren’t as good as them.

Before the return at Highbury, Patrick Vieira confronted Gary Neville – Neville deemed one of the biggest culprits of fouls in the first game.

Kevin McCarra in the Guardian summed up the evening.“There were allegations and recriminations, fouls and dives, but the deepest impression was left in the minds of the crowd rather than on the bruised limbs of the combatants: United were markedly better,” he wrote. “It should be a while before anyone dares argue that Arsenal are still a more evolved species of football team. With an extra man deployed in midfield they eventually dominated as Roy Keane had one of those nights when power somehow surges through his ageing body. His first confrontation took place even before the game had started. Tempestuous ill-will was spawned in Arsenal’s defeat at Old Trafford in October and the Highbury tunnel proved to be an overflow area for that animosity prior to kick-off. Keane squabbled with Patrick Vieira and the captains had to be lectured by the splendid referee Graham Poll.”

In the tunnel, Keane confronted Vieira for what he’d said to Neville, causing the home players to become visibly unsettled. “I’ll see you out there,” Keane told his rival.

“I meant it,” he wrote in his second book. “I love the game of football. We’d sort it out on the pitch – no hiding places… we went out and played like Brazil.”

This was a significant evening for the likes of Rooney, Ronaldo and Darren Fletcher, who were all outstanding, if not quite as good as Keane.

In individual games United were still a match for anyone but the transition of these younger players meant patience was needed while they ironed out the inconsistency.

Keane was absent for another of those inconsistent moments – in September 2005, he broke a bone in his foot in a draw at Liverpool and was forced to miss a couple of months. As he recovered, he was still required to do club duties as was tasked with the punditry job for MUTV after a 4-1 loss to Middlesbrough. Keane was predictably scathing – United did not air the tape as Keane had been critical of some of the younger players.

This was a different era of football already, perhaps not quite as equipped to deal with Keane’s blunt honesty as his team-mates five years earlier, although according to most parties they seemed to handle it well when the tape was shown.

“Look, lads. Have any of you got a problem?’ They were all, ‘No, no, no,’” Keane said. “I’d said something about my wife tackling better than him, for one of the goals. But I could tell from his expression that he was fine with it; Fletch knew my form. The mood was still good between me and the players. But Carlos and the manager were in the background, steam coming out their ears.”

Wayne Rooney, in his Sunday Times column, agreed. “I’ve watched the video and there’s nothing wrong with it at all,” he said in 2020. “He said that players can’t pass the ball ten yards and they’re playing for Manchester United and it’s not good enough. Well, he’s right.”

It should be said that Rooney, like Keane, had a fall-out with Ferguson – Keane’s a little more spectacular, as he apparently criticised the manager for his involvement with the horse-racing controversy that had tied into the takeover of the club, and had also had confrontations with the assistant manager Carlos Queiroz.

The moment, and the tape, caused Ferguson to effectively sack Keane in November 2005, a few months before the end of his contract.

The relationship did not initially seem sour – Keane went to Celtic and had a testimonial at United a few months later, and when he became manager of Sunderland, he worked with Ferguson to get a number of former players from the club.

But both then released second autobiographies in 2013 and 2014, in which the warmth and respect of the first versions had almost completely disappeared. The relationship is still said to be acrimonious, which is a shame, as there was no player who represented the manager more perfectly than Roy Keane.

The first version of Roy Keane became the best midfielder in the country. The second became the best of his generation and cemented his place as the all-time best Premier League midfielder.

The third influenced the next generation, setting the minimum standard that the likes of Fletcher, Rooney and Ronaldo all personified in Ferguson’s last great team. Without Keane, that attitude would not have been so dominant, that is for sure.

Like Eric Cantona before him, Keane inspired the present and the future, extending an influence far beyond his own 470 appearances (which places him at number 12 on the all-time list).

He was that rare example of a player greater than the sum of his talents – a player who would grace any team in United history and improve it.